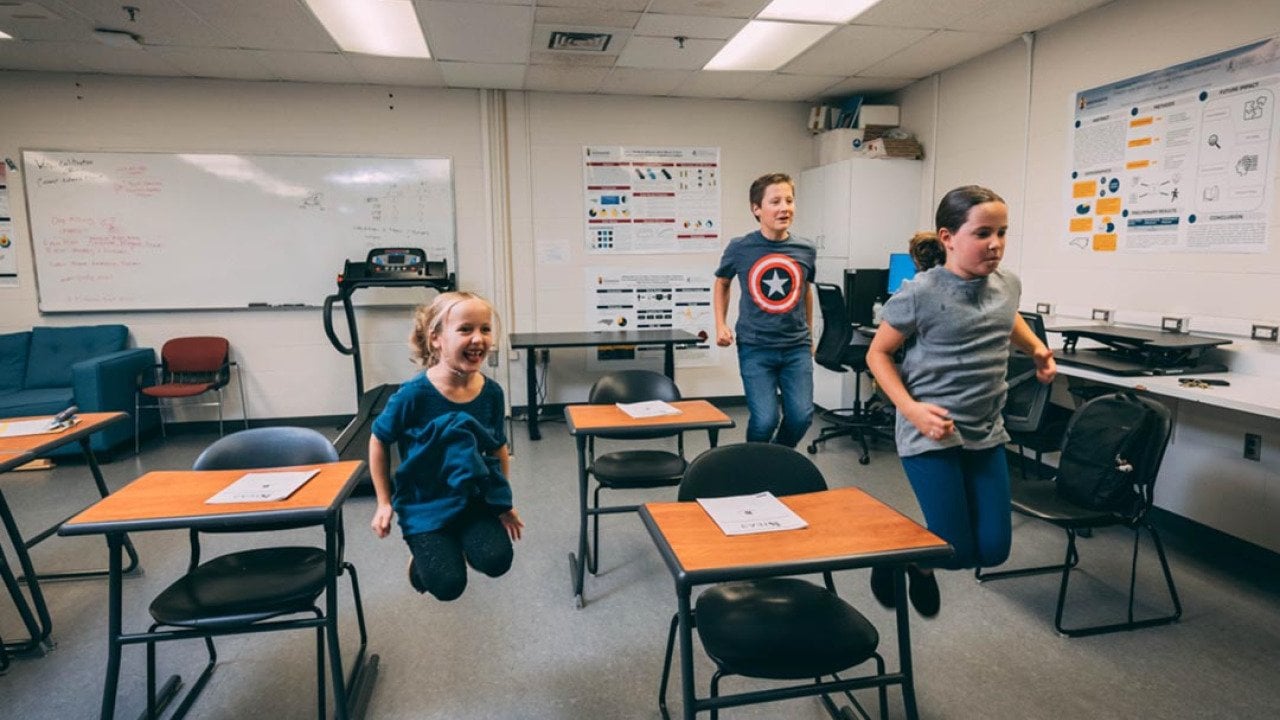

Jumping jacks, lunges and squats, and better test scores

Courtesy of UNC Greensboro University Communications

When Kusum Sinha, the superintendent of Garden City Public Schools in New York, took a trip this summer to Finland, Estonia and Sweden with other district leaders, she came back wishing she could build out more time in the school day for physical activity.

What she saw in Finland was especially “eye opening” — a recognition of the value of play in a child’s educational journey. The schools she visited enjoyed a 15-minute break for exercise or physical play for every 45 minutes of instruction time.

“I thought, how can I replicate that here? We don’t do enough of it.”

“We’ve really worked hard, especially at the K-5 level, to bring kids outdoors as much as possible,” said Sinha, who in years past has directed funding to develop multiple outdoor classroom spaces across the district’s five elementary school buildings. Educators are encouraged to incorporate movement breaks into snacktime, and they recently fenced the schoolyard around the middle school so that older students can enjoy a recess and be more active.

But when it comes to boosting physical activity, any significant alteration to the daily schedule comes with a cost: precious lost minutes required for core academic classes.

“I do think if kids had that extra physical activity, we’d need to teach less,” Sinha said. “It’s weird to say, but I think they retain more when they have more opportunities to be active.”

She’s not wrong.

New research from the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, shows that when students engage in high-intensity interval exercises, they score significantly higher on standardized tests measuring verbal comprehension. In a study of elementary school children aged nine to 12, researchers examined a type of brain neuroelectrical activity called “error-related negativity,” which occurs when people make a mistake and is associated with reduced focus and performance. What they found is that after acute exercise, the error-related activity decreased significantly, The 74 reports.

“We have to be aware of our child’s health, and if we want them to succeed academically and mental health-wise, exercise is something that needs to be in the forefront,” says Eric Drollette, the study’s lead author and a professor at UNC. “Yes, it helps with their physical health, but we can’t forget the brain part of it. The benefits of exercise can be influential in an [educational] environment .”

Drollette had a pretty good idea that the experiment would reveal some type of positive relationship between exercise and academics. After all, research has long borne out the benefits of physical exercise on the mental health and general wellness of adults and children alike. One of Drollette’s own previous experiments involving college students who underwent high-intensity interval training showed improved brain function and cognition.

But having three children of his own, he knew anecdotally that any type of prolonged high-intensity activity, like running on a treadmill or using other types of exercise equipment, just wasn’t feasible for younger children. Not only, he suspected, would they get bored or lack motivation to complete the exercise, but it also wasn’t a scenario that educators could easily replicate in their own classrooms.

The goal instead was to design a fitness regimen that would hold student interest and could be performed in the classroom without taking up too much time. What he came up with was a series of stationary exercises – think high knees, jumping jacks, lunges and squats — performed one after another, alternating between 30 seconds on and 30 seconds off for nine minutes total.

“This is more natural for a kid’s type of exercise,” he said. “I wanted to make sure that if a teacher reads this, or if the public reads this, they can say, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s something that’s possible to do in the classroom.’”

What ended up surprising Drollette, he said, was how selective the benefits were for certain academic achievements — most notably, for word recognition and fluency, which include reading and word processing — and much less for math. Another surprising result? The children didn’t realize they were exercising as hard as they actually were, suggesting, Drollette said, that they truly enjoyed the movement break.

The study comes against the backdrop of schools shortening recess and physical education classes in order to prioritize instructional time and boost academic achievement — especially in the wake of the pandemic, which wrought steep learning loss. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children should get four 15-minute recesses every day. While more than 90% of the country’s elementary schools incorporate regularly scheduled recess into each school day, on average students receive just 27 minutes.

As it stands, only eight states require schools to offer a daily recess, and most districts don’t have a formal recess policy. Since the mid-2000s, up to 40% of school districts have reduced or cut recess. Moreover, some districts still allow educators to take away recess as a punishment, which experts say does more harm than good.

While Drollette acknowledges that the main focus of schools is academics — not movement — the practice of shortening recess and physical education, he says, is short sighted.

“As a nation, we’ve really struggled to recover loss in physical activity since the pandemic,” he says. “If we keep removing physical activity, we may be hampering mental health as well as cognitive function. And then if kids are performing poorly cognitively, they’re not doing well with academics, causing schools to keep pushing academics. And so my approach is that we may need to flip the other direction. We need to focus on physical movement for a better healthy mind in order for kids to do well in school.”

This summer, the Trump administration appeared to recognize as much, issuing an executive order establishing a President’s Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition, as well as reinstating the Presidential Fitness Test — the latter of which harkens back to back to the 1950s under President Dwight D. Eisenhower but was phased out in 2013.

“For far too long, the physical and mental health of the American people has been neglected. Rates of obesity, chronic disease, inactivity, and poor nutrition are at crisis levels, particularly among our children,” the order reads. “These trends weaken our economy, military readiness, academic performance, and national morale.”

Courtesy of UNC Greensboro University Communications

It’s unclear what the new regimen will look like, but the original test required students to compete in their schools and nationally by completing circuits of pushups, pullups, situps and the mile run, among other exercises. Notably, the test was retired under the Obama administration in exchange for the “Presidential Youth Fitness Program,” which focused more holistically on student health and less on the competitive test.

Starting this school year, one thing is certain: School district leaders like Sinha and classroom educators will continue to be hard-pressed to inject more time for physical activity into the day due to time requirements for core academic subjects.

“Physical activity is more important than ever before for our students,” she says, noting that students in Finland traditionally score at the top on the international benchmark assessments known as PISA — far above students in the U.S. “It’s always been important, but kids are different today, and they need to be moving their little bodies around.”

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

![]()